A Confusion of Runtimes

If you count the original broken python version I made back in high school for an english project, I've been working on how to make text adventure games for almost four years (by no means continuously). And I only just realized the fundamental error in how I've been going about it. It's mostly a misunderstanding of the words “runtime” and “tool”, but I'd like to start at the beginning. All the way back in eleventh grade.

HighSchool

The original version of A Night in Algiers actually does one thing better than my attempts to improve it. It separates the data from the code. All the dialogue is stored in a JSON file and the python script basically just retrieves a string from that file, using the player's input to navigate through the keys and tables. I think this is where the trouble began. Because even after moving from python to C# and from JSON to … C#, the idea of storing object's information in keys and tables persisted.

Take Two

Now I'm going to cut myself a little bit of slack here, since remaking A Night in Algiers was my first time using C# outside of Unity. I remember being a bit confused on how to structure the project, but I don't know why I didn't google something like “object oriented best practices” or read through some dotnet tutorials. Instead, I made the bold choice to disregard everything I had ever learned about what classes, methods, and fields are and kind of acted like I was still fetching things blind from a JSON like database.

The codebase is absolutely littered with dictionaries, and with methods like AddExit, AddObject, SetCommand. To indicate that the

character Marie is swimming at the start of the game there's the line marie.conditions.Add(“swimming”, true). Essentially I had

implemented my own, worse, slower, not-compiler-checked fields. While making this version I did manage to learn some pretty fancy

things about functional types, higher order functions, and lambda expressions, however I demonstrated a pretty glaring lack of

understanding of the fundamentals.

The other thing I failed to understand at this point was what exactly I was even attempting to make. As of writing, the description on Algier's github page says it's “a bare-bones but powerful tool for writing parser-based interactive fiction in C#”. While not technically wrong, I think the mindset that I was making a “tool” that makes games was incredibly unhelpful. I'll come back to that later.

Take 2.0

After A Night in Algiers came Session21 and Algiers 2.0. I don't think too much changed in the Algiers namespace at the structural level. I pulled some kinda cool tricks involving player state and peanut bowls, but underneath a lot was the same. I finally remembered what classes were, though, so the game specific parts look a thousand times better. We've got inheritance, actual fields, actual methods, the whole shebang. I was trying to do everything “right” this time. Unfortunately, I didn't really know what that meant, so the system was still far from well-designed. If only there was some sort of place where I could learn how to design software...

Oh Look, He Took one College Course

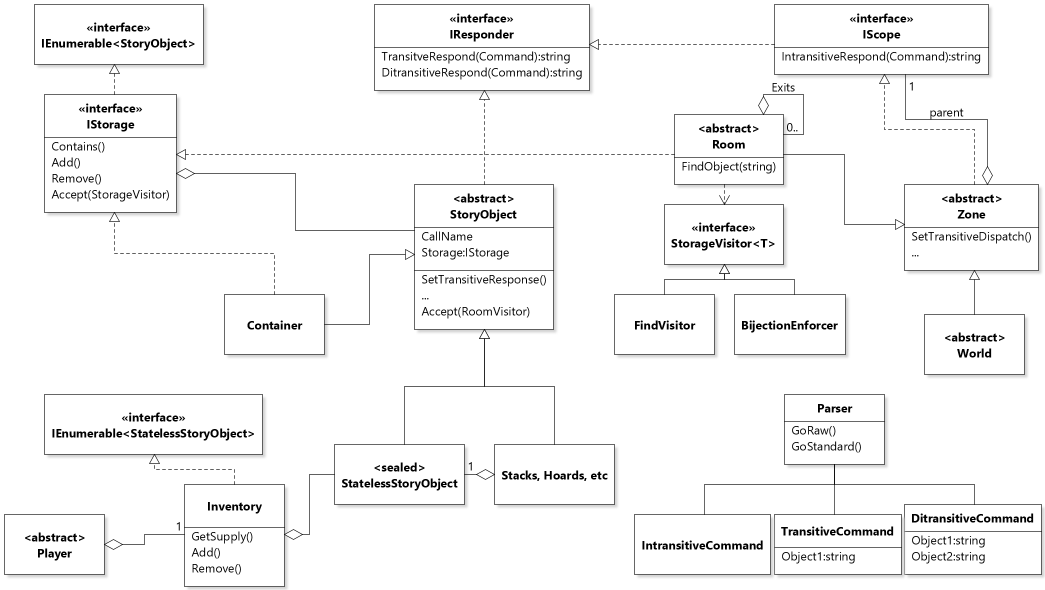

It was called “Software Design” and the textbook is actually a pretty good read if you're looking for a nice intro to the topic. With those three credits under my belt, I turned my attention back to Algiers and went to work. I drew up a UML class diagram, used interfaces over inheritance, threw in some visitors, composites, and decorators – the works.

(I actually am very proud of this diagram)

The goal was to make something nice enough that people other than myself could use it (in theory, that is. I was under no illusion that anyone else but me would be interested in a new interactive fiction tool at this point). I thought maybe I'd even work up to building a real GUI desktop application, but I thought I should start off with a code-based version. So with most of the heavy lifting out of the way, I started making a little test game. At first everything looked very promising. Thanks to my redesigns, the compiler actually knew quite a bit about the objects I was working with and could provide its helpful little autocompletes and scrollovers. “This is great,” I thought. “My users are going to have such a nice time using this tool.” But then I realized that something still wasn't popping up; something was still hidden to the compiler. One set of dictionaries had persisted: the responses.

Runtime

When a player types a command, the parser turns the first word or phrase into a command object, which it uses to retrieve a string-returning-function from a dictionary stored in the target object. Being stored in a dictionary, the compiler doesn't know what responses exist and so can't make any of it's little suggestions (and perhaps more importantly, can't check if your retrieval will fail until runtime).

After cleaning everything else up, this was unacceptable. I needed the compiler to know everything, so my imaginary users could have the best possible experience. Fortunately, I knew what to do. “Well,” I thought. “Why are we even storing funcs in dictionaries? Let's just make a bunch of interface methods that correspond to the different commands and then call them from a big switch statement on our command objects. After all, just like a field that describes if a person is swimming, there's no need to add a category of response at runtime. By the time the game starts all of this stuff is set in stone.”

Ok. Problem solved, right? For one specific game, sure. But this was supposed to be a tool for making games, or at the very least a self-contained library other programmers could use to make their own games. And the way all the inheritance and implementation shook out, I couldn't see any reasonable looking way to make compile-time responses work without exposing the guts of library.

This shouldn't have come as a surprise. If you take another look at the diagram, it is clearly describing the structure of an actual game, not of a tool for making games. For a specific game, things like what commands are valid are pretty darn integral, and it makes sense for them to be a part of some high level interfaces. For a game-making tool, though, commands (along with most game-specific attributes) are in fact variables that need to be able to change at runtime as the developer builds up the world of the game.

It took this moment for me to realize that I had been trying to cram two totally different processes into a single runtime for years. All those dictionaries actually start to look reasonable if you're in the process of making a game. Of course you can't just store things in fields, you don't know what fields you need yet! By the time you actually start playing the game, though, the compiler better know what's going on.

So What's Next?

A big reason of moving away from having everything be dictionary keys and values was to reduce the crosschecking that needs to happen. If the compiler isn't keeping track of what all our variables are called, it's easy to forget one or to make a typo and never notice until runtime. So a purely code-based tool would be a big pain to use. A nice GUI that let's you just see all the objects you've defined so far and click and drag everything around sounds like a much better option. Once you're done, this program could take the information it's been given, turn it into some C# code that looks like more like my latest attempt, and then produce an executable.

That sounds like quite the project, and I'm not sure when I'll get around to taking it on. But I think if Algiers is going anywhere, that's where it's going.